Time for a ‘moon shot’ effort over Los Angeles storm water

Posted on | December 21, 2012 | 4 Comments

Los Angeles shimmers after the rain. Even the asphalt gleams. But the smut and litter washed away won’t simply have vanished. Rather, swept up by rainwater, it will have become embroiled in a torrent of grime before being flushed into storm drains, LA’s rivers and finally the Pacific.

Los Angeles shimmers after the rain. Even the asphalt gleams. But the smut and litter washed away won’t simply have vanished. Rather, swept up by rainwater, it will have become embroiled in a torrent of grime before being flushed into storm drains, LA’s rivers and finally the Pacific.

Anyone who has been around for a couple of voting cycles will be forgiven for wondering: Didn’t we already pass Proposition O in 2004 precisely to fix that? Didn’t a $500m bond filter our dregs once and for all?

We did and it didn’t. While Prop O money bought grates that now trap trash at many if not all curbside catch basins, and its combination of actual dollars and inspiration value led to a few new “green streets,” capturing the sheer magnitude of toxins and trash that are indiscriminately flushed into the ocean by rain in Los Angeles will take a collective effort more daunting than the moon shot. In recognition of this, a tax is being proposed to begin the long, slow process of cleaning up LA’s rinse cycle.

Flyers explaining the Clean Water, Clean Beaches measure – and offering property owners the opportunity to protest what amounts to a new parcel tax — have been reaching potential voters with uneven success.

Supervisor Michael Antonovich, who opposes the measure, protested recently that it was easily mistaken for junk mail. He worries about messy administration of the fee by dozens of Southland cities, the Los Angeles County Flood Control District and as yet to be formed “watershed area groups.” As Antonovich’s planning deputy Edel Vizcarra noted recently, “You already pay a Flood Control tax.”

LA County residents do indeed already pay for flood control. Every time a house doesn’t flood or wash away in a winter rain even though it is built on a flood plain surrounded by some of the steepest mountains in the US, it’s a product of a $60-odd dollar a year fee rolled into an annual property tax bill. But when the Flood Control District looks at pollutants in storm water, its response is, in effect, “Not my job.” The district was founded in 1915 expressly to divert rain from structures and catch some for the local water supply if it could. With the help of the US Army Corps of Engineers, it took half a century to fit the basin with storm drains and paved rivers that receive the runoff from sudden, often hard rains. That it became a pollution delivery system for the Pacific Ocean was an unintended if not unforeseeable consequence. Now that a clean up is needed, Flood’s position is best summed up by this press release issued over a recent Supreme Court court case in which it argues that it is responsible for managing flood waters, but not for the quality of the water pouring into its storm drain system and, hence, the pollutants spewing out of it.

So if cleaning up our storm water isn’t Flood Control’s job, whose job is it?

Nobody quite knows. Not long after Flood Control and the US Army Corps of Engineers more or less finished the storm water flushing system for the L.A. basin in the 1960s, the impact on beaches became evident. Passage of the Porter Cologne Act in 1969 and federal Clean Water Act in 1972 led to the gradual setting of pollution limits, first for obvious dumpers — factories and so on — but more recently looking at the diffuse flow of urban grime whose origins are so universal that no one local government in LA County’s patchwork of 88 cities can check it. For background on this, this California Research Bureau history explains how clean water legislation and lawsuits, a seminal case being led by the Natural Resources Defense Council and Heal the Bay, led to the setting of modern pollution limits, called Total Maximum Daily Loads.

Complying with TMDL limits may ultimately mean rewriting building codes to reduce or eliminate run-off and rethinking no less than our entire road system, which was kitted out with street-side catch basins and storm drains to double as a storm-water disposal network during rains. As watershed activists and cities grapple with the problem, potential fixes identified include cutting use of lawn chemicals and stopping car work on streets, landscape tweaks directing roof water to gardens, retrofitting roads to absorb rain into groundwater, and creation of infiltration grounds so the cleaner water can be banked in local aquifers for municipal use and insurance against seawater intrusion into groundwater. Given that the task involves updating policy and planning ordinances of the 88 cities making up LA County, it only makes sense that a super agency such as Flood Control, which is part of the county’s public works department, would administrate the funds secured by the Clean Water, Clean Beaches measure.

And so, irony of ironies, Flood Control is fronting the new pollution abatement measure, while at the same time arguing before the Supreme Court that it doesn’t do pollution.

Those of us who have long hoped for a culture change at Flood Control are pleased by the mission drift, however briefly incongruous it might seem. However, Supervisor Antonovich has another concern, a valid one. This is over what role and what powers the State Water Resources Control Board might gain in these shifting times. Formed after the passage of the Porter Cologne Act, California’s water quality control boards are meant to regulate wastewater discharges. It’s arguable that if LA’s local water quality control board did its job well then this new Clean Water, Clean Beaches measure would not be so badly needed. According to a recent LA Times report, its proposed new methodology for enforcing pollutant limits involve ways for polluters to escape penalties if they manage to be seen to be attempting some sort of remediation.

Which brings us back to the Clean Water, Clean Beaches measure, which, if its funds are misused as window-dressing, could be just the thing cities need to escape board fines for lackluster pollution control efforts. Still, in spite of skepticism from Supervisor Antonovich and fellow supervisor Don Knabe, after public comments are heard by supervisors on January 15, it’s likely that the ultimately deciding ballots will be mailed to homeowners next spring.

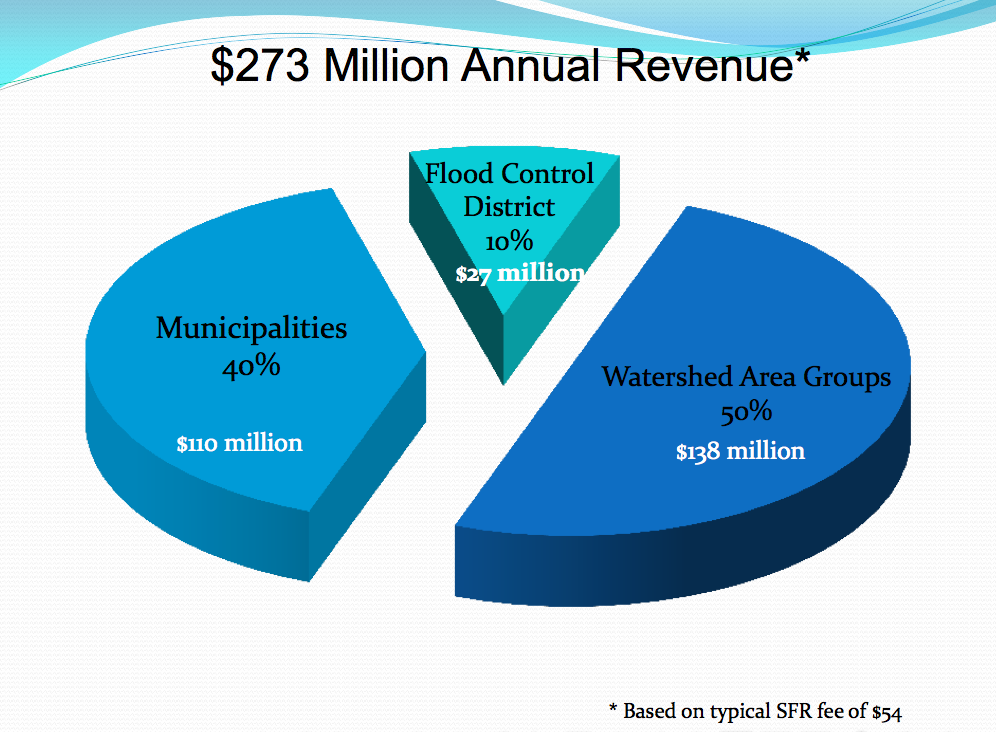

To explain the measure, Flood Control has posted breakouts of the potential fees in which homeowners could expect to pay another $20 to $84 a year. The cost would be more for larger and predominantly paved commercial properties. Divided between the Flood Control District, 85 cities served by the district and “watershed area groups” that need to be formed to deal with water flowing across city boundaries, the projected $200 to $300 million raised every year will go to projects such as the Garvanza Park storm water capture system and Elmer Avenue “green street retrofit.”

Curb cuts direct storm water into garden swales, where it irrigates new plantings in this July 2010 photo of Elmer Avenue. Rain barrels, gardens with permeable paving and back flow preventers make this a Rolls Royce storm water retrofit.

What rain rushes past a block of curb cuts diverting water for gardens on Elmer Avenue is stripped of debris by catch basin grates before entering the storm drain system.

Both projects are models of rain capture and examples of the kind of local water harvesting that Southern California must do and do often to cope with population growth and climate change. The question then becomes: What will it take to Garvanza-tize and Elmer-ize LA County? Here the sheer scale of the task becomes staggering.

Using back of the napkin math, $415 billion should do for the entire county what roughly $1m did for Elmer Avenue’s 10th of mile run in Sun Valley.* Because Elmer Avenue was a Rolls Royce retrofit with lots of eco-equivalents of bells and whistles, it’s reasonable in the make believe world of estimates to halve it to $207.5 billion. To put this number in proportion, even adjusted for inflation, that reduced cost is still roughly twice what it cost to get to the moon. But while the Apollo program took less than a generation, if the clean up of Los Angeles County storm water is restricted to only funds taxed under the Clean Water, Clean Beaches measure, completing the task might take 691 years.

This begs the question: Is the enormity of the problem really a lack of money? Or is it a lack of leadership, flexibility and progressive thinking? Why, for example, is water quality a separate line item with separate tax base than all other road work? Why is any work done on a road anywhere in LA County without every time it’s possible incorporating storm water curb cuts to irrigate street trees?

So, should LA County property owners vote to tax themselves with this new Clean Water, Clean Beaches measures in spite of uncertainties, bureaucracy, and costs normally associated with space shots and foreign wars? We should. We can fix administrative problems. We can’t fix the Pacific once we kill it. LA is world famous precisely because of its beaches. Its marine life dazzles and delights. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, LA’s beach economy infuses the county with more than $2bn a year. Who in their right mind would refuse to spend $300m and accept losing $2 billon?

Supporters of the measure such as the Arroyo Seco Foundation stress that the economic boon goes beyond protecting existing economies. Think of all the green jobs new Elmers and new Garvanzas would bring to LA! But the first round of new work must be at all the most visible and instructive places. It was equal parts heart-breaking and maddening when earlier this year the City of Los Angeles decided that it couldn’t afford (or couldn’t be bothered to implement) state-of-the art storm water BMPs in its new City Hall landscape. Few see Elmer Avenue besides the several dozen Sun Valley families who live on it. Millions see LA City Hall.

If we pass this Clean Water, Clean Beaches measure, and I have my eyes, fingers and toes crossed that we will, its limited funds must go to integrating clean water standards into all of our codes so pollution abatement isn’t a special line item. No agency, least of all the ones charged to disperse storm water and monitor its pollutants, should be allowed to pass the buck. No city receiving funds should be allowed to do any kind of street work that doesn’t meet new, best standards. All roadwork, not just million dollar-plus watershed projects, should meet storm water Best Management Practices. Curb cuts are not so expensive that county and city public works departments couldn’t be doing them right now, every time any roadwork is undertaken. And here is where Supervisor Antonovich must be respected in his dissent: It is unspeakably cynical to carry on using public money building polluting structures while holding hands out for new money to change their ways.

But it would also be unspeakably cynical of us not to back the Clean Water, Clean Beaches measure because moonshots don’t happen without Apollo-scale investments to get them off the ground and enthuse the public. We have a massive, life or death challenge before us to save our most precious amenity, the Pacific. We must rise to it.

For more information on the Clean Water, Clean Beaches measure, click here. For the best reporting on this, read Steve Scauzillo in the San Gabriel Valley Tribune.

*For lack of a published estimate of how much it would ultimately cost to retrofit Los Angeles County streets with green storm water catchments, I improvised. Starting with a City of Los Angeles inventory citing 6,499.5 miles of street within 470 square miles, I applied that scale of density across LA County Flood Control District’s metropolitan service area of 3,000 square miles. This produced the estimate that LA County might contain 41,489 miles of street, excluding freeways. Applying the cost of the Elmer Avenue retrofit, which was roughly $1m for a tenth of a mile, I then calculated that retrofiting all county streets to Elmer Avenue standards could cost $414,893,617,021.28. Then I halved it because Elmer Avenue is fully loaded with storm water catching devices that might not all be used on all streets. For anyone tempted to use this figure, please understand that it’s a very rough guess. Suggestions on how to improve it, or where to find an official county-wide street inventory or more scientific storm water retrofitting cost estimate are most welcome.

Tags: Clean Water Clean Beaches Measure > Heal the Bay > Los Angeles County Flood Control Division > Natural Resources Defense Council

Comments

4 Responses to “Time for a ‘moon shot’ effort over Los Angeles storm water”

Leave a Reply

December 25th, 2012 @ 10:09 am

A glitch left the comment function of this post disabled in the first days after publication. Of e-mailed comments received, one long-time water watcher said:

“I don’t trust that the funds will be administered well. The county should have been able to present the public with actionable, specific and budgeted plans for how they’d use the funds so that property owners know exactly what they’re getting. There’s been over a DECADE of watershed planning including $million+ studies so there’s really no excuse for vagueness. I felt the same way about Prop O, which manifested as a bit of a pet projects fund. I believe the funds are carved up for different things here too, without too much specificity.”

December 26th, 2012 @ 12:18 pm

Another old hand in the watershed politics of Los Angeles, whose organization was part of the Elmer Avenue project wrote by e-mail:

The one thing I’d point out that gives us heartburn every time we hear it is the Elmer Avenue price tag. Its expense was as much the result of it being a first-of-it’s kind project as much as it was because it had all the bells and whistles. As you point out, when this type of work goes to scale, we think (and hope) that an economy of scale will grow to match it and prices for some of this work will begin to drop. Contractors will learn how to be green and efficient at the same time. Actually, they already are…

December 29th, 2012 @ 8:51 pm

If only this initiative would empower people/builders to house-by-house eliminate run-off. This could be done by making run-off illegal for new construction, as it is in many states (you have to produce/implement plan that shows how you will prevent water from leaving your land), and when remodeling is embarked upon, and by major subsidies to homeowners for installing underground sumps/rainbarrels and other larger-scale run-off collecting devises. Of course educational campaigns would have to accompany. When you show people real benefits both to themselves and the environment produced by bmps, and provide subsidies encouraging them to do so — then most get on the band wagon.

One such low tech initiative, low-flush toilets has saved more water than almost any other single item, and it was accomplished house by house, business by business, through rules on new construction and subsidies to change out the old water hogs.

I haven’t finally decided if I’m personally supporting this new attempt, although my gut reaction is “of course! This is needed!”

Antonovich is probably correct in not trusting the county to do the right thing with new money when it consistently ignores laws on the books, even when there is already money set aside to implement local water management projects. I’ve experienced this directly and recently. When we had a chance to see the Woodbury Median design almost a year before it was built, we pointed out that the design did not comply with the County’s own LID (low impact design) guidelines. We were given song and dance about all the reasons (money, money, and money) curb cuts and other bmps encouraging infiltration were not integrated into the design. And this on a project I had had listed with IRWMP (Integrated Regional Water Management Project) 7 or 8 years ago precisely BECAUSE its topography offered incredilbe potential both for infiltration and channelling of water to Arroyo Seco settling ponds. Hundreds of millions were set aside for IRWMP-listed projects. There is and was supposedly money in the pot for precisely this kind of project (some just came through for the Arroyo Seco Foundation in Hahamongna). But the county either doesn’t follow up, apply, or otherwise pay any attention to opportunities to do the right thing. Why would we think this fuzzily written new “plan” with no details or accountability engineered into it will be any different?

We should definitely do a public education workshop on this with Altadena Heritage.

January 6th, 2013 @ 10:04 am

As far as supporting the effort to retrofit streets during street repairs, I could only support a fee for this if it was open to competitive bidding. Living in the Mid City area, I’ve observed too many one block road repairs lately undertaken by LA street services crews where one guy works while four others stand around watching. It recently took the city over a month to resurface a 3 or 4 block length of Washington near I-10.