Thunk tank

Posted on | January 18, 2010 | 7 Comments

Next Monday, the US House of Representatives Subcommittee on Water and Power will be holding a local hearing at the Los Angeles offices of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. The subject?

Next Monday, the US House of Representatives Subcommittee on Water and Power will be holding a local hearing at the Los Angeles offices of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. The subject?

“California drought solutions.”

If that seems an odd thing to be contemplating during a deluge, it’s not. Most of our water does not come from local rainfall, but from other places, which, if not in a drought, are definitely in a jam. Last week, that jam became orders of magnitude worse as Sacramento judge Roland Candee struck down something called the Quantification Settlement Agreement.

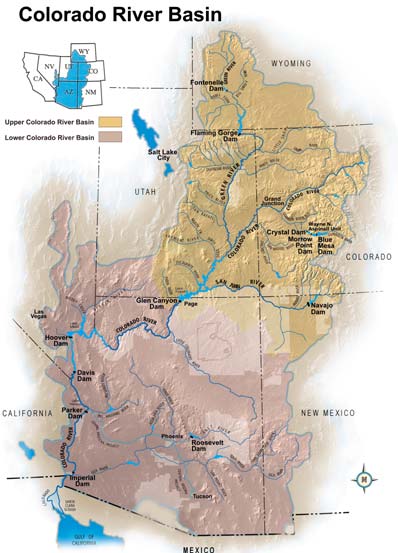

This 2003 wad of contracts profoundly affects how California may legally divide and manage its share of the Colorado River, which is along with Owens Valley in the Eastern Sierra and the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta in Northern California one of the three main sources of fresh water for Southern California.

Candee’s voiding of the QSA last week is scary for at least two reasons. First, Southern Californian cities could lose vast amounts of water secured in trades under the agreement. Second, and, most nerve-wracking for this writer, the geniuses behind the QSA are in many cases the same brains behind the much-vaunted package of bills that we’re told will “fix” the ailing Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. These bills are due to come before California voters in November in the form of an $11bn ballot measure.

This is the point where the enviably young and even more enviably oblivious may benefit from crib notes. During the 1990s and well into the noughties, Southern California managed to explode into one contiguous suburb, in part because of the relatively low demands on the Colorado River by other states further up the system. Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico remained fairly empty places while Arizona, Nevada and California filled up with sun-seekers.

As northern states grew fractious about how and if Phoenix, Las Vegas, San Diego and Los Angeles could ever be unhooked from river flow once they became dependent on it, Clinton interior secretary Bruce Babbitt entered the scene. California was the thirstiest state for what was then “surplus” Colorado River water, at the golden state’s most gluttonous drawing more than 800,000 acre feet in a year, or enough for 1.6 million homes.

To the delight of the rest of the states on the river, Babbitt began the push to bring California within its legal allocation.

In spite of its huge overdraft, this should not have been onerous. While California has the shortest frontage on the Colorado River, it claims far and away the most water, more than a fifth of the entire flow. But in the 1990s, as Southern Californian suburbs steadily devoured chaparral, most of that huge river allocation didn’t go to the region’s fresh carpeting of lawn and asphalt.

Instead, it went to farming interests in the California Desert, the big daddy of which is the Imperial Irrigation District.

One must get to a history book or Google page to understand why farmers growing lettuce in an inferno have priority water rights dating back to the Gold Rush. Suffice it here to say that they do, and that those rights are inviolable under the present laws governing the river and west.

So, as Babbitt, followed by George W. Bush’s interior secretary Gale Norton, kept pushing to wean California from surpluses, the problem facing cities from Los Angeles to San Diego became: How to wrest ag water from Imperial for suburbs to make up the difference?

A daring (if politically suicidal) thing would have been for Clinton and Babbitt to revisit the laws and compact that endow Imperial. What emerged instead throughout the late 1990s and early noughties was the Quantification Settlement / Joint Powers Authority Agreement.

Under this, trades of agricultural water to cities such as San Diego were allowed in return for, among other things, an open-ended commitment by Californian taxpayers to deal with environmental remediation of the Salton Sea, a lake formed by an overflow of the Colorado River into the California Desert in 1905 and now highly polluted by agricultural run-off — from the Imperial Irrigation District.

This is where the Candee decision last week makes particularly frightening reading. (This excerpt has been edited to remove footnotes and spell out acronyms. For the full decision, click here.) As the decision shows, getting the deal through the US Congress and the California legislature took extraordinary maneuvering, which left California taxpayers holding an indefinite and open-ended bill for remediation of the Salton Sea.

Why is this frightening? Pick your poison. Two presidents and two interior secretaries, seven states and the California legislature all became embroiled in a deal that did nothing to address the underlying causes of the crisis, while the agreement that they did reach was fatally flawed.

It did little to curb growth. A year before the QSA was signed, there was a record low year on the Colorado River, sharpening the belief that its flow had been overestimated and what is now called a “drought” might become the new normal.

Smarter states might have curbed development, but growth galloped on throughout the 1,400-odd-mile-long river system in ever more mind-boggling ways. Only recession in 2009 slowed the drive, by which time Las Vegas had invented the mega casino replete with pina colada-scented volcanoes while demanding the right to drive a 300-mile pipeline to the foot of Nevada’s only national park and pump the Great Basin dry. Utah’s big idea became a pipeline from Lake Powell so it can create a slot-free resort in its southern desert. Denver is torn between tunneling through the Rockies to find new water, or running a 500-plus-mile-long pipeline to Wyoming.

It doesn’t seem to have occurred to anyone in any of these places that development might be best done near viable water supplies or that the dry west has natural limits for development. Suggest that the region needs to revisit the compact and laws that allocate the water of the Colorado River, including the mind-boggling Imperial endowment, and water managers will laugh in your face.

Even on the water-rich side of the Sierra rain shadow, California can’t manage plenty. Just as the QSA has been revealed as a sham, and Imperial’s gluttony is validated by archaic Western water law, we are going to the polls in November on a series of water bills designed to fix our other main water supply, the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta.

Laugh, cry, move to somewhere wetter, but believe it: Among the architects of the plan to save the Delta are many of the same brains behind the QSA.

Some more history for the young and fragrant: Just as the QSA was being completed, California woke up grumpy and decided to can Governor Gray Davis. It took his successor, the self-styled “reformer” Arnold Schwarzenegger, less than two years to hire Davis’s former cabinet member, utilities player Susan Kennedy, as his chief of staff. Kennedy is widely seen as the Karl Rove to the Austrian body builder’s Bush as it pertains to the new water bills.

These new bills bring with them a sickening echo of the QSA. While the QSA was sold as a boon for the Colorado River, this new Kennedy-Schwarzenegger package of bills was put to California’s legislature last fall in the most dramatic terms. They were the only way to secure the fragile and clearly sinking Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta from earthquakes. The fresh water supply of 24 million people was at stake.

That, pass the cyanide, happens to be true, but once the bills were passed, the resulting documents didn’t first fund Delta restoration, but devoted the initial $4bn or so to new dams favored by the governor and his intimates in the cigar tent.

No one should be surprised that the chief of Denver water announced last week that he is moving to Hawaii to grow nuts. The pressing question is: Can he take 17 million south-westerners with him?

The person bringing the House committee hearing west next Monday to discuss our “drought” is local 38th District Congresswoman Grace Napolitano. I have no doubt that Rep. Napolitano is sincere. In fact, I unreservedly applaud her public spiritedness, which in itself is remarkable and refreshing. This is in no way to equate her or her efforts with the above-described corruption.

This is merely a long way of saying that we created this “drought” and any solution to it cannot take an ever-longer road around the cause.

This post has been updated. Note: this post has elicited an interesting comment string from smart people. I urge visitors to read it. I have been rightly and smartly challenged to enumerate the cross-over minds between the QSA and recent legislation, and have offered entire agencies, the biggest of which are Reclamation, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the San Diego County Water Authority. One might as well add the California water bar, but that would take some time.

Comments

7 Responses to “Thunk tank”

Leave a Reply

January 19th, 2010 @ 10:09 am

Laugh, cry, move to somewhere wetter, but believe it: Among the architects of the plan to save the Delta are many of the same brains behind the QSA.

But who do you mean? I’m really asking, because in general, I don’t see the same names working on Colorado and Delta issues.

January 19th, 2010 @ 10:12 am

I read your piece, but am curious whether you’re thinking of more people than Susan Kennedy.

January 19th, 2010 @ 10:46 am

I’m one of those who worked on the state policy reform package — but not on the QSA or the water bond. I think it’s important to note that the reforms in the package of bills passed by the state legislature on November 4 are largely independent from the water bond.

For example, the water conservation requirements and additional Delta protections in the package will be in effect whether or not the bond is approved by the voters.

January 19th, 2010 @ 11:05 am

Good question. I did not elaborate on this point because of the constraints of space and time. There are many of the same bodies beyond Kennedy, the biggest being Reclamation, the second biggest the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. If they’ve done a better job with the pending bills than the QSA, I’ll be delighted. But I’m skeptical. Candee’s description of the rush to get the QSA passed was all too familiar.

January 19th, 2010 @ 11:23 am

It’s this passage from the Candee decision that is so reminiscent of the recent rush on the water bills:

While the State Water Control Board proceedings were underway, attempts to reach a final agreement on the QSA and related agreements by the end of 2002 continued. The “Key Terms” of a possible QSA had been agreed upon in 1999; and Imperial Irrigation District, Coachella Valley Water District and Metropolitan Water District of Southern California had jointly issued proposed QSA documents for public review in 2000.

Various draft agreements and public meetings and workshops occurred in 2000 and 2001, but the majority of intense QSA activity took place in late 2002, from November through December. In December 2002, Metropolitan and Coachella Valley water districts approved one version of the QSA and related agreements, while the Imperial Irrigation District and San Diego County Water Authority approved a different version.

Metropolitan and Coachella rejected the Imperial / San Diego version of the QSA and related agreements. At the end of 2002, there was no mutual agreement upon the proposed QSA contracts. Different views on cost issues, environmental mitigation funding, and termination events continued to separate the parties.

Tremendous pressure existed to get this QSA deal done by October 12, 2003. This is reflected above and in the state legislative history of which the Court has taken judicial notice as requested by the San Diego County Water Authority documenting that: “The history of the QSA has been that periodically, the affected parties announce that they had reached agreement on terms, the Legislature takes action to make the necessary changes in law, and then for one reason or another, the agreement falls apart at the last minute. While by all appearances, the outcome will be different this time, there are no guarantees. Consequently, the three QSA bills are contingent upon enactment of each of the others, so that none of the bills will become operative unless both the other bills become operative by January 1, 2004. More important, the principle benefits to the QSA parties of these three bills are contingent on execution of the QSA by October 12, 2003. October 12, 2003 is also the constitutional deadline for the Governor to sign or veto bills passed this year.”

The legislation itself contains this October 12, 2003 deadline.

The wording of the QSA Joint Powers Authority Agreement (Contract I) was not settled on at the time of the Imperial Irrigation District Board’s formal approval on October 2, 2003. The addition of the language found in the second and third sentences of clause 9.2, the last sentence of clause 10.1, and clause 14.2 of the QSA JPA Agreement, show that the QSA JPA Agreement — and because of their interrelationship and the critical nature of the QSA JPA Agreement, the entire QSA — still had substantive terms remaining to be negotiated as of October 6, 2003.

The Court additionally finds that the lack of any draft QSA JPA Agreement in the administrative record at the time of the Imperial Irrigation District Board meeting and the timing of the Department of Fish and Game Director E-Mail (Exhibit 1) show that material portions of the QSA JPA Agreement were still being negotiated days after the October 2, 2003, approval by the Imperial Irrigation District Board.

The Department of Fish and Game Director E-Mail shows that the State was concerned on October 6, 2003, about entering into an agreement that would amount to writing a “blank check” on behalf of the State.

January 19th, 2010 @ 1:24 pm

On the public record and I have continued the discussion in e-mails. In fairness, they should be posted. With OtPR’s permission, some more back and forth on whether or not I met my burden of proof in claiming the same geniuses behind the QSA are involved in the new water legislation:

OtPR: I saw your answer, but I don’t follow the reasoning (that dangerous thinkers who created the QSA are also behind the water legislation). Met and Reclamation are huge; just because they have people in both negotiations doesn’t mean they’re the same people. I would believe that Reclamation doesn’t have any crossover staff; I’d bet anyone who worked on the water legislation came out of their Mid-Pacific Branch, which is involved in the Delta, but stops at the Tehachapis. (That’s why I never got into the Colorado River stuff; Mid-Pacific doesn’t touch it.) You’d have to go up to the Undersecretary level to get someone who does both Delta issues and Colorado issues, and that would be an appointed politician who probably doesn’t craft deals or legislation.

I’d bet money that Met has two separate branches for Colorado River stuff and California stuff. I don’t know any people who are versed in both. I’d be even more surprised to hear that the same people are writing big agreements like the QSA and the recent water legislation. Unless you know the names of actual people who are prone to write bad agreements (and I was hoping you were breaking a story about former CALFED executives), I don’t think you’ve got hold of anything here.

I don’t mean to be discouraging; I’ve enjoyed your syntheses and reporting. But that premise seems underdetermined to me.

EG: Not discouraging. May I post your response, or would you? I agree that I didn’t meet my burden of proof and spoke sarcastically of “geniuses” instead of agencies. I’d have to spend more time than I have to name names and not agencies, but I’d bet a bottle of something drinkable that within Met there is serious crossover. Ditto San Diego County Water Authority and ditto the California water bar. I don’t have time to trace back Sen Feinstein’s part in the QSA legislation, but I’m thinking there’s probably history there too. Given time and a time machine, I’d go back and speak in terms of agencies and process and not people. Instead, I’m left trying to pull and bait and switch and say, er, the same process and same agencies that brought us the QSA look to be the same players behind the new water bills.

OtPR replies: Sure, you’re welcome to post it. I’ll say also:

I’d agree that the same process and same agencies that brought us the QSA (and maybe Monterey Agreement?) are involved in the new water bills. (Although I kinda also think they’re the universe of involved folks, so they’re going to show up in everything major.)

As I read your email, I realized that I’ve got a sampling bias. You are almost certainly right that there are lots more people in SoCal that know the Colorado system and the Delta both. Up here, people can get away with knowing the Delta and neglecting the Colorado system. If they’re very interested in the Colorado system, they focus on it.

Keep up the good work!

EG replies: Thank you. I have been busted and deserve it.

January 26th, 2010 @ 11:55 am

[…] the glorious panelists is what seemed to be a decision to simply ignore the recent voiding of the Quantification Settlement Agreement. Calvert worked hard on it, he […]