High good, low bad: Mead in June 2010

Posted on | July 1, 2010 | 2 Comments

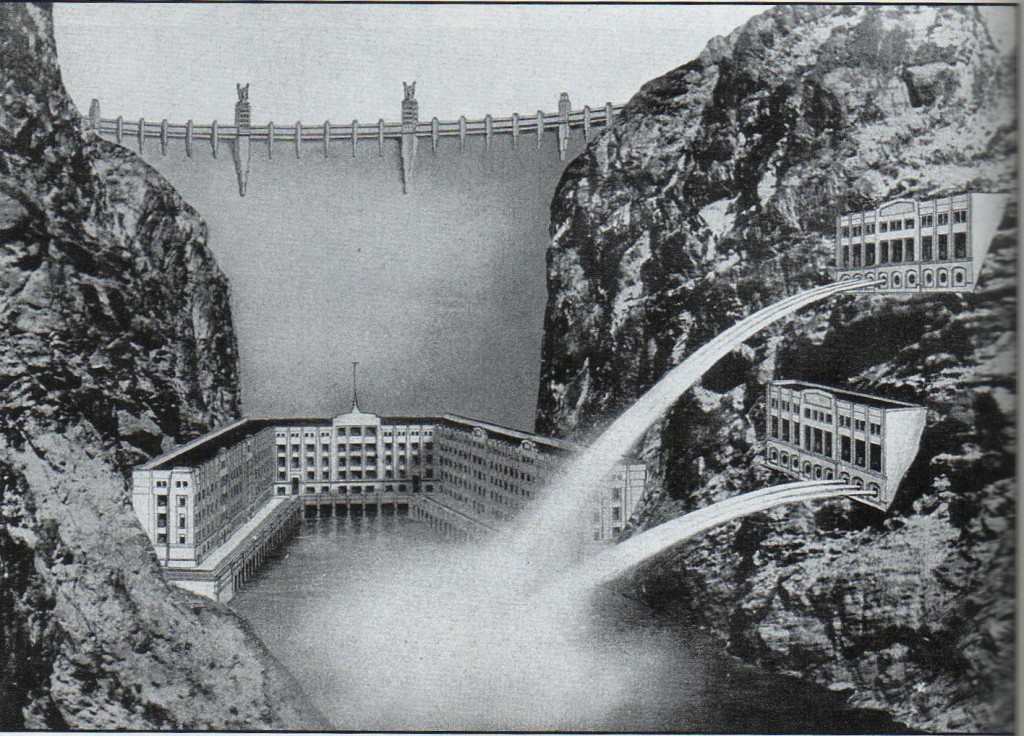

'Colossus' author Michael Hiltzik speculates that Los Angeles Times proprietor Harry Chandler was behind the Hoover administration's hiring of architect Gordon B. Kaufmann to streamline and simplify plans for Boulder (eventually Hoover) Dam. "Early in 1931, Kaufmann began hacking away at Reclamation's architectural scheme (above)," writes Hiltizk, "which was burdened with such neoclassical gingerbread as pediments, elaborate balustrades on the dam crest, and columns capped with bronze eagles." Click on the image to be taken to the Reclamation page about Kaufmann, who also collaborated with the bureau on Parker and Shasta dams.

There is a telling quirk to most US maps of the Colorado River: They stop at the Mexican border. The river’s once-mighty delta and the Sea of Cortez rarely figure.

Save a few forays south, this delineation holds true in the recently published book “Colossus: Hoover Dam and the Making of the American Century“ by Michael Hiltzik. Rather than expand the range of the official narrative about the Colorado and dam that gave rise to the modern Southwest, Hiltzik mines well-studied areas for neglected detail.

Here the Los Angeles Times reporter strikes rich veins, offering vivid accounts of the settling and selling of the California desert, later the “Imperial Valley,” and the emergence of the doctrine of prior appropriation, our proudly impossible system of western water law born of the Gold Rush. Long, loving and often fascinating chapters are devoted to the political wrangling behind the Colorado River Compact and the Boulder Canyon Project Act. The alacrity with with Colorado’s Delph Carpenter realized that California’s six rival states on the river needed to act to protect their water is breathed back to life with flair and insight. A diversion into what became Arizona’s institutional truculence among the seven states on the river produces in George Hebard Maxwell a proselytizer whose emotional heat and extreme xenophobia would not be out of place in the state’s current immigration battles; yes, the rightful father of the Central Arizona Project was palpably nuts (and, Hiltzik nicely points out, a native Californian).

Highlighting interesting spots in this book could take a long time. Hiltzik’s chronicling of the dam’s construction is so studded with detail that he even devotes a page to obstacles faced by the Oregon-based landscape architect (Wilbur W. Weed) hired to bring roses and lawn to Reclamation headquarters in Boulder City.

That said, no review would be complete without touching on Herbert Hoover’s part in this dam, which is tenderly traced; if you haven’t felt sorry for the man most publicly held responsible for the Great Depression before, you might after reading this book. After more than a decade of heavy lifting to get the river states to stop quarreling and the dam built, the 31st president of the United States suffered the harrowing indignity of stepping into the shadows as his political rival and successor, Franklin D Roosevelt, inaugurated what was then the largest dam in the world.

That said, no review would be complete without touching on Herbert Hoover’s part in this dam, which is tenderly traced; if you haven’t felt sorry for the man most publicly held responsible for the Great Depression before, you might after reading this book. After more than a decade of heavy lifting to get the river states to stop quarreling and the dam built, the 31st president of the United States suffered the harrowing indignity of stepping into the shadows as his political rival and successor, Franklin D Roosevelt, inaugurated what was then the largest dam in the world.

Anyone seeking to understand how Los Angeles, San Diego, Las Vegas and Phoenix sprang from arid land should read “Colossus” — it is a mighty history for a colossal dam. But be warned: This strength is also its weakness. This very good book holds a strongly backward and often conventional gaze. The storied, exquisite and mysterious desert setting is described, when it is described, as a wasteland. It’s hard not to wince when tribes are bundled with endangered species, as if the rightful place of native Americans is being lumped with amphibians, flowers and all that. Mexico is but a back yard fence. Water left to flow its course is regarded as wasted. Then, grating for this reader, there is the ever-present issue of California’s narcissism and ingrained sense of entitlement. Hiltzik does a fine job sketching a balance of power so off kilter in the West that California could convince feds to build a dam in Nevada to bring the fresh waters of Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico largely to serve Los Angeles and the gloriously self-styled Imperial Valley of the California desert.

He further shows us how the Southwestern sunbelt was eventually born of a river whose flows were over-estimated, then over-allocated (and 20% of which evaporates every year), but offers little discussion of how it might survive its own formidable design flaws. As fascinating as it is to learn that Hoover Dam’s reservoir, Lake Mead, reached its all time record elevation of 1,225.44 feet on July 24, 1983 (and that the spillway concrete suffered), Hiltzik will need to write a sequel to address how to cope with the likes of Lake Mead’s elevation in July 2010, which opened today at more like 1,089 feet, or roughly 136 feet lower.

*This post has been updated. Random thoughts have been added and the closing elevation checked against Reclamation records.

June 2010: 1,089.30

June 2009: 1,095.26

June 2008: 1,104.98

June 2007: 1,113.50

June 2006: 1,128.26

June 2005: 1,140.46

June 2004: 1,126.93

June 2003: 1,143.19

June 2002: 1,160.19

June 2001: 1,183.12

Click here for complete elevation records from the federal Bureau of Reclamation.

Tags: chance of rain > Emily Green > Lake Mead elevations > US Bureau of Reclamation

Comments

2 Responses to “High good, low bad: Mead in June 2010”

Leave a Reply

July 1st, 2010 @ 9:30 pm

“…there is the ever-present issue of California’s narcissism and ingrained sense of entitlement”

Now there’s a thought that should illuminate all writing having to do with California and the Colorado River!

August 9th, 2010 @ 7:42 pm

The media just won’t tell about the manipulations of the dams’s levels since the 2007 compact deal. The ramifications of this deal are huge locally and internationally. Not to mention all the other water myths and profits policies that need examination. A new messaging strategy is needed.