Expo Line plants: Think first, proselytize later

Posted on | June 4, 2012 | 10 Comments

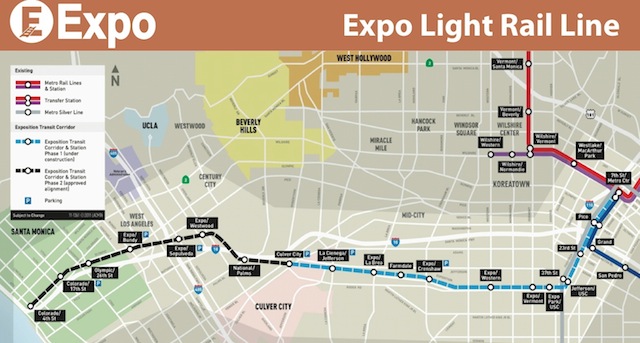

UPDATED Many of the same people whose passion and stamina forced Los Angeles City Council to adapt a low-water garden for City Hall are now campaigning for Phase Two stops of the city’s Expo Light Rail Line to be landscaped with native plants. Their movement, called LANative, has a website, a petition, and, most recently, support from an impassioned article in the Huffington Post.

Fellow travelers in the native plant movement, forgive me, but I can’t sing with the choir on this one. I can’t see how most of the powerful arguments for natives at City Hall to do with water efficiency, beauty, sense of place, pollinator benefit, run-off capture, leading by example etc. necessarily apply to a railway, which is less a garden setting than a fierce border twixt track and asphalt, steel and concrete.

In fact, as Phase Two of Expo Line construction presses forward, the most logical question might be: Why landscape around trains at all?

Leaving aside native-vs-exotic plant choices, the placement is backwards. This bike park puts trees where they will confer the least shade to people and cause the most problems on the tracks, while leaving a tangle of shrubbery limiting space and access for bike parking. Click to enlarge.

The Huffington Post column extols the beauty of native sages, toyons, fuchsias and bunch grasses. They are lovely landscape plants, yes. Think of the pollinators, it urges. Always a pleasure to picture birds, butterflies and bees. Funnily enough, years ago, observing a Volvo mow down a swallowtail was what first seeded now-rooted skepticism about use of any nectar- or seed- or berry- producing plant in a high traffic area. Isn’t using natives in the treacherous medians between trains and roads the horticultural equivalent of putting an ice cream truck in the middle of a freeway?

The Expo setting combines the worst aspects of traffic medians with all the problems of foundation planting, a style of landscaping where shrubs and trees are jammed up against structures and descending open space is given over to lawn or paving. As the best kind of Mediterranean landscaping teaches us, the exact opposite arrangement should be pursued. Structures should be kept free of plants, water, weeds etc and shrubs and trees should be massed away from buildings in enough open space for their water, roots and branches not to be an obstacle or even contributor to structural decay. This also prevents planting from becoming fire hazards and trash pockets and makes for more efficient, less heat-stressed irrigation. Wildlife benefit by not being constricted to heat-blasted spaces often narrower than an IKEA wardrobe. In the case of rail lines, planting done to buffer noise should be done across the street from stations. Shade for stations themselves should come from built shelters, ideally covered with solar panels.

The Expo setting combines the worst aspects of traffic medians with all the problems of foundation planting, a style of landscaping where shrubs and trees are jammed up against structures and descending open space is given over to lawn or paving. As the best kind of Mediterranean landscaping teaches us, the exact opposite arrangement should be pursued. Structures should be kept free of plants, water, weeds etc and shrubs and trees should be massed away from buildings in enough open space for their water, roots and branches not to be an obstacle or even contributor to structural decay. This also prevents planting from becoming fire hazards and trash pockets and makes for more efficient, less heat-stressed irrigation. Wildlife benefit by not being constricted to heat-blasted spaces often narrower than an IKEA wardrobe. In the case of rail lines, planting done to buffer noise should be done across the street from stations. Shade for stations themselves should come from built shelters, ideally covered with solar panels.

The planting bed around this station will become a tangle of weeds, and source of run-off if watered, or dead zone if not. Click to enlarge.

Lawn next to the train line will prove a constant water, energy and maintenance suck. Placement of the trees next to the track will make leaf fall a nuisance. Click to enlarge.

Watching the argument over the Expo Line landscaping play out is fascinating on a second level. It offers a near-perfect snapshot of one of LA’s most abiding culture wars between conventional and native landscapers. I’ve met hundreds of native plant enthusiasts over the years on the Theodore Payne Foundation tours. I myself am one. Usually we are home gardeners, nursery owners or landscape designers. Invariably our lives have been transformed by switching from lawn to native wonderlands vibrant with wildlife. Our water bills are half that of a conventional family. We do not torture our neighbors with mowers and blowers. The best of us are not just environmentalists, we are also artists. We fill LA up with flowers, scent and color. And, as if it needs mentioning, we’re quite often smug.

At the other end of the spectrum from the native plant community, which will no doubt feel betrayed by this, we have the conventional facilities industry that has clearly done the Expo landscaping so far. They garden with lawn and exotic trees and shrubs. They come bearing sprinklers and mowers. They’re high-carbon, high-noise, high-water types who make environmentalists like me despair. And along the Expo Line so far, they’ve done what they always do: Use ghastly little pockets of grass, hedges and exotic trees to fluff out unlikely spaces.

To my eye, when it comes to the Expo Light Rail Line debate, both sides are showing their weakest hands. The call for use of sages, toyon, grass and fuchsia shows no awareness about context, or animal welfare, maintenance, fire resistance and ease of litter-picking. Beyond pollinators being lured to squash and splatter zones, what about the large and vulnerable populations of feral mammals forced to take refuge in ever more perilous ribbons of un-buzzed greenery? Human safety doesn’t seem to figure, either. Would anyone want to be on a rail carriage when a spark hit a dry stand of bunch grass? How could maintenance crews get to the tracks for quick repairs? Who will litter-pick among the dense foliage? Where are the skilled gardeners needed to tend these plants?

To judge by what the conventional landscapers have done so far, they know even less about trains than they do about horticulture. Flick through a slide show of stations already greened up around the edges and you have a dictionary of how to waste water, energy and time on unsafe plant choices. As someone who spent two decades commuting on the London Hammersmith Line, I can assure Angelenos that “leaves on the track” is not announced to commuters because the leaves look pretty. Here in LA, it takes only mild gusts to turn palm-lined streets into bone-yards of huge, jagged, hard fronds. Fronds on the track will be no joke. And there clearly will be fronds on the tracks. As for the irrigating and weeding of those awful little beds, why? If you’re having nervous decorative impulses to soften a harsh urban setting, why not use sculpture? Something that doesn’t need watering, weeding and pruning?

Our failure to use and celebrate the indigenous flora extolled by LANative in the parks and open spaces where it belongs has left the region the horticultural equivalent of a city with more tourists than residents. We’ve all heard the expression, “there’s no there there.” In Los Angeles landscaping, the problem is that there’s no here here. The native movement is so desperate to change that, it’s fighting for marginal spaces with what in the Expo Line case is a marginal argument. But if plants must be made to endure inhospitable and unnatural beds between roads and rails, the choice should be parsed very carefully. It should be an ebullient salute to the great moment for LA when 21st century public rail transport pierced the East-West divide. It should be safe, regionally appropriate, low-maintenance and, above all, beautiful.

*The Expo Board of Directors will be meeting in Room 381B at Los Angeles County Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administra

UPDATE: 6/5/2012: the passage about foundation planting and link explaining the lawn-centric style of planting that undermines thinking about LA landscaping was added, along with more photos.

Comments

10 Responses to “Expo Line plants: Think first, proselytize later”

Leave a Reply

June 4th, 2012 @ 2:54 pm

Good points. And a native landscape will bear an extra burden of criticism for looking crappy if it’s not well maintained.

June 5th, 2012 @ 6:18 am

I STILL respectfully think it is better than nothing. I’d rather see the effort spent elsewhere but right now urban southern California is effectively a post-apocalyptic wasteland. At least maybe a mycorrhizal spore will be able to use this area.

I totally agree about the palms – whether the native variety or not – bad idea. I disagree about the fire concern because horticultural native plants aren’t really any more flammable than anything else unless you really choose the wrong ones (maybe chamise and unirrigated sage wouldn’t be good)…

I just wouldn’t push for less native plants or less plants ANYWHERE around LA. That’s more water running off, more pollution, more urban heat island, more of the miserable existence of trodding through the concrete wastes expecting no beauty or novelty or emergent nature in your life. Basically, this is a tiny piece of remedy to why I left California and why it pains me to return even for a short time. These native plants don’t make sense from a habitat or pollination ecology standpoint. They will offer little to even an urban landscape. What they are, though, is a tiny sense of place and uniqueness in a landscape where both of the above were systematically, inexplicably annihilated down to the last poppy, for reasons I struggle with and to this day am no closer to understanding. Here in Vermont, I wonder why people plant Norway Maple, a tree which looks almost identical to sugar maple until fall when the leaves turn a much duller color. Also it makes no sap. But here people at least celebrate and enjoy the sugar maples and I am seeing them planted again. In southern California there is little celebration of toyon, instead planting of toxic, sickly oleanders and invasive, floppy, ugly myoporum.

I suppose there are places where poorly-done native plant landscaping might turn people off to native plants… but it seems most people won’t even realize the plants are native plants until they come across them on a hike or wander as well.

On an somewhat unrelated note, does anyone know why along the ‘new’ part of the 210 near Ontario, a bunch of neat oaks and bunchgrasses and such were planted in the mid 2000s and then ripped out a year or so later and replaced with hideous lantana or whatever? I was so pissed when that happened but I even asked about it at some policymaker meetings and never got an answer. Worst!

June 6th, 2012 @ 5:08 pm

I like the idea of compromise.

There are many low water plants that will offer beauty, thermal cooling, and absorb rainfall. Why not mix a blend of smaller scaled California Natives that will look great all the time and can bear improper maintenance with some even sturdier succulents? A simple tree/leaf mulch or accent of gravel mulch that would create a sense of sculptured space would work beautifully.

So many possibilities!

..zauschneria, agave, festuca, smaller arctostaphylos, eriogonum grande rubescens (smaller buckwheat and incredibly hardy), salvia Daras Choice…and on and on.

Enven in the confines of this narrow space, plant material would be beneficial.

This is a can do! Again, this is a design problem that is actually quite easy to solve.

June 6th, 2012 @ 5:33 pm

Thanks for the thoughtful comments, everyone. I like the idea of compromise too but I don’t think I’m going to do much here but so offend people that a kernel of thought might be seeded for some job in the future. That’s OK for me, not so good for the pollinators. I’m thinking succulents are probably the best bet, if there’s room and if they can use sorts that seldom flower. But my bottom line is I don’t think foundation planting will give more than it takes in terms of water and maintenance. Why garnish train stations? Run-off can be dealt with by engineered solutions. The further problem (my biggie) with the plants listed in the post and the zausch, arcto and eriogonum suggested in a comment is that all are pollinator magnets. Hummingbirds love zausch and come in low to cat and car zones for it. Buckwheat is a butterfly crack. Splat. Arcto: it’s winter sustenance for hummers. And of my many objections to industrial foundation planting, the chief one might be luring pollinators into such deadly territory where traffic is lethal, trimmers and blowers also deadly, and the only water might be in puddles or street run-off. I think the animals and insects will suffer — badly — if they establish at all. But on this we can bet: They will try. These plants have magnificent wildlife allure. So we should landscape with them in places fit for wildlife. Says I! I have no illusions that I will win friends or influence people with this, and it may amount to systematically alienating my gardening community, but I dissent from the tribe so completely, so profoundly here, cutting up rough was necessary. I think using natives in these settings is a kind of default, unintended cruelty. Feel the same way about flowering medians. In the be careful what you wish for territory, we should be careful when we invoke wildlife benefits. The causes should actually benefit wildlife. Next thing you know, we’ll be zoning highway medians as wildlife sanctuaries.

June 7th, 2012 @ 10:24 am

Native plants should be everywhere, and particularly at light-rail stations where there is great potential for public education about the benefits of gardening with natives.

Your concerns about might happen with the installation of native plants are just as valid for any kind of plant and are precisely the kinds of issues that should be solved in the design process: the plantings, whatever they may be, should not be dense; trees should be placed where people gather rather than overhanging rail lines. All these are good design principles, and they can be realized with native plants.

Los Angeles has precious little free urban space and we need to jump at this remarkable opportunity to brighten new public places and educate the public about what to do in their own communal and private spaces. To abandon this opportunity because of wildlife losses is to miss the point entirely: It is like deciding not to reintroduce wolves because a rancher might shoot some of them. The net boon to the environment hugely outweighs the losses. And while it is sad for any creature to die, it strains credulity to argue against habitat restoration because some of the expanding populations of species will indeed die. The alternatives are far worse: continued losses and one more missed opportunity to demonstrate how native plants are an important part of living within our geography and climate.

The Expo Line is not a marginal location for native plants. Every “problem” you anticipate can be solved through intelligent placement and overall design. The Expo Line is a prime location because of its visibility and the number of people that will pass through the stations every day. It is in many ways more important than the private backyards of native-plant aficionados because the careful, planned urban landscapes will greatly broaden awareness of the possibilities and importance of supporting native habitat.

June 7th, 2012 @ 12:14 pm

Good comment, Lisa, thank you. I’m glad to hear design considerations entering the argument.

I’m lost by the allusion to wolves. There’s a wild west’s worth of difference between wolf rehabilitation programs in Wyoming, say, and calling for use of natives jammed between rails and roads in urban LA because of their importance to pollinators. I’d love to see some of the hyperbole leached out of this. I’ll try at this end.

The point of the post wasn’t to argue against natives in public places. It was to ask native aficionados to stop, to think deeply and critically about how collectively LA can get the most benefits in terms of cultural identity, messaging, beauty, shade, water quality etc, for the least water and carbon-intensive maintenance in public spaces, be they city halls, libraries, schools, parks, flood control basins and, so potently, the river. Are railway stations really great planting zones? Is it worth fighting for? Or is it a waste of political capital? Light rail stations are everyone’s favorite places right now, Hooray for trains! But are they really fit for planting?

The railway line – native argument as first posed ignored the design challenges. It sang from a familiar crib sheet: Natives! Pollinators! Water conserved! Run-off prevented! Maintenance saved! My point is that the first argument should have been design-led: What’s the cost? What’s the benefit? What are the limitations? How much water will you import for these beds? How much rain will they trap? But instead the urban greening community went in chanting, “Natives!” “Insects!” “Water!”

Yes of course my argument applies to non-natives as much as natives — it states that clearly and I’m grateful that you underscored it. At the core, my question isn’t natives or non-natives — though pollinators may suffer worse with natives and that was a point — my basic question has to do with foundation- and median- planting. Is this ecologically or environmentally sound? Should we be doing it at all? It is rare in the Mediterranean, where they have cleaner design sensibilities. It is rare in the Southwest, where they have less water than we do thanks to our early mastery of the water grab. My question is: Should it be rare here, too? I’d love to see the native movement think hard before fighting for it. It’s an arm of landscape architecture that became rote as part of the rise of lawn culture. It’s fussy, high-cost, high-maintenance. And dangerous. At any rate, it merited kicking out the idea that it may not be a good fit for a changeover to more sustainable landscaping, particularly around rails. It should be questioned, deeply before arguing plant choices.

June 7th, 2012 @ 1:26 pm

I wonder if many of the native plant advocates have the Orange Line (North Hollywood to Woodland Hills and now Chatsworth) busway/bikepath landscaping in mind, a mix of natives and other plants, where CNPS was an effective advocate. I believe the Orange Line landscaping is wider than what’s available on the Expo Line, though some of your concerns might also apply there. I think the bike path should have been wider to allow safer separation between walkers and bike riders, which would have made it a better draw in getting folks out of their cars, but would have reduced the landscaping somewhat.

June 7th, 2012 @ 1:36 pm

Taking a look at the Expo Line photos, I see that the Orange Line does have much more space.

For the Expo Line, I’d definitely like to see native plants if possible, but the priority for any transit line should be on making it **and especially its adjacent bike path** attractive, safe, and convenient enough to draw people out of their cars, and low cost/low maintenance so that we can replicate it. That might have more effect in the long run on reducing sprawl and saving native plant habitat, not to mention creating better human habitat.

June 7th, 2012 @ 2:25 pm

Hey, BC. What interesting points, all. I particularly like the point about drawing people out of their cars. As to the question, will water conservation generate more sprawl? Possibly. Builders are certainly right there in line insisting on maximizing their appropriations. But conservation does increase the likelihood that environmental quotas will be met (and hopefully raised.) It also reduces the amount of energy it takes to pump and treat water, going in and coming out, which is a huge hidden cost.

June 8th, 2012 @ 12:12 pm

I whole heartedly agree with your commentary Emily. Planting native materials in the interstitial spaces will amount to little more than ‘parsley around the pig’. Planting natives in this narrow buffer will appear like a weed patch, unattractive and neglected.

It is delusional to think that there is an ‘educational’ component to this kind of planting unless someone takes the time to install labels for what the materials are, how much water is being saved, etc.

What is needed are shade trees to create a comfortable environment, not an ineffective foundation planting.