The Dry Garden: Heirlooms by trial and error

Posted on | July 3, 2010 | No Comments

A tomato left to rot in the garden last summer resulted this spring in my eating ripe homegrown heirloom tomatoes by Memorial Day instead of the normal harvest time around the Fourth of July. A fruit dropped in mulch sprouted in October rain, did nicely through winter storms and then, with some watering since May, the vines have been yielding what I’ve decided must be Cherokee Purple tomatoes for going on a month. In terms of flavor, they’re not Black Krims. No other tomato is. The word online is that Cherokee Purples rival Brandywines. That is true. In other words, they’re good enough that, with heirloom tomatoes of this quality costing $3 a pound in farmers markets, I thought I might be on to manna for readers. So I rang UC Davis’ C.M. Rick Tomato Genetics Resource Center to ask why every gardener in Southern California doesn’t plant tomatoes with their poppies — in the fall.

A tomato left to rot in the garden last summer resulted this spring in my eating ripe homegrown heirloom tomatoes by Memorial Day instead of the normal harvest time around the Fourth of July. A fruit dropped in mulch sprouted in October rain, did nicely through winter storms and then, with some watering since May, the vines have been yielding what I’ve decided must be Cherokee Purple tomatoes for going on a month. In terms of flavor, they’re not Black Krims. No other tomato is. The word online is that Cherokee Purples rival Brandywines. That is true. In other words, they’re good enough that, with heirloom tomatoes of this quality costing $3 a pound in farmers markets, I thought I might be on to manna for readers. So I rang UC Davis’ C.M. Rick Tomato Genetics Resource Center to ask why every gardener in Southern California doesn’t plant tomatoes with their poppies — in the fall.

Click here to keep reading this week’s “The Dry Garden” column in the Los Angeles Times.

A creative commons for school gardens

Posted on | July 2, 2010 | No Comments

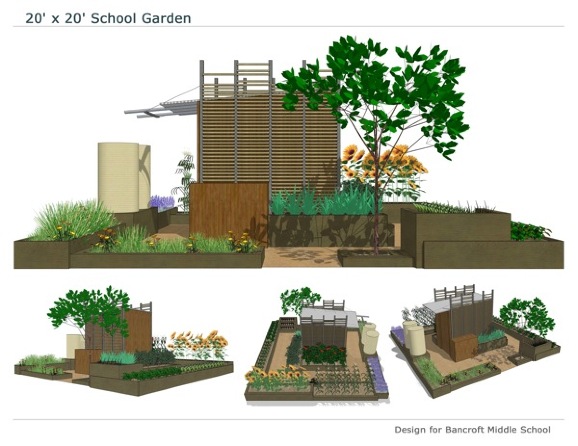

Good Magazine today announced the five finalists in its school garden design competition. Click on this shortlisted entry by Joseph Sandy of Arcadia, California to see all of the designs. Before giving you the account of competition organizer and Good writer Alissa Walker, a note. As a judge in the competition, it was thrilling to see the thought and creativity that went into 40 submissions. It was perhaps even more exciting to be involved in such a beautifully conceived competition, which set guidelines that should be achievable by any campus. Kudos in this department is probably due to Mud Baron, Green Policy Director for LAUSD Board Member Marguerite LaMotte, and a man who has seen first hand what works and what doesn't, then set out to promote and popularize the best approaches. From Walker's announcement: Finalists will attend a one-day workshop with landscape architect Mia Lehrer to refine their proposals. Working closely with LAUSD, proposals will be matched to local schools due to site appropriateness, maintenance resources, and available funding. Designers will be encouraged to participate in the building of the gardens. One garden will be installed in a Los Angeles school by October. Simultaneously, the designs, processes and a best practices manual will be shared widely through GOOD's community, website and magazine, and distributed under a Creative Commons license. Further, all 40 designs considered by the judges will be made available as a "40 great ideas" guide for anyone hoping to start a garden at their school.

High good, low bad: Mead in June 2010

Posted on | July 1, 2010 | 2 Comments

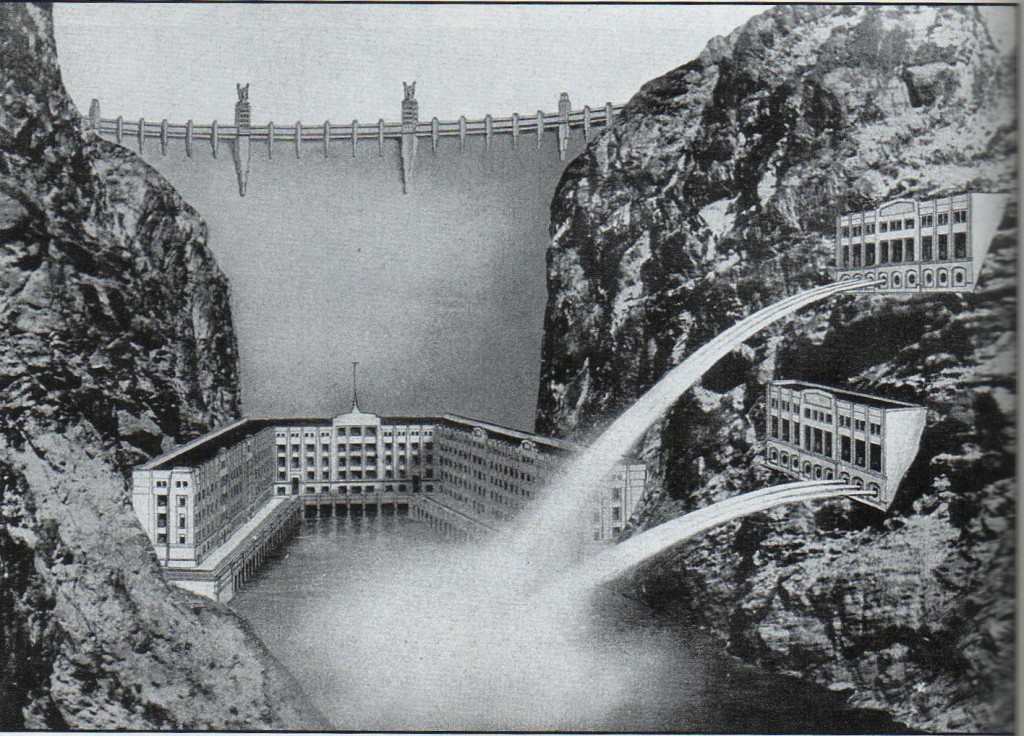

'Colossus' author Michael Hiltzik speculates that Los Angeles Times proprietor Harry Chandler was behind the Hoover administration's hiring of architect Gordon B. Kaufmann to streamline and simplify plans for Boulder (eventually Hoover) Dam. "Early in 1931, Kaufmann began hacking away at Reclamation's architectural scheme (above)," writes Hiltizk, "which was burdened with such neoclassical gingerbread as pediments, elaborate balustrades on the dam crest, and columns capped with bronze eagles." Click on the image to be taken to the Reclamation page about Kaufmann, who also collaborated with the bureau on Parker and Shasta dams.

There is a telling quirk to most US maps of the Colorado River: They stop at the Mexican border. The river’s once-mighty delta and the Sea of Cortez rarely figure.

Save a few forays south, this delineation holds true in the recently published book “Colossus: Hoover Dam and the Making of the American Century“ by Michael Hiltzik. Rather than expand the range of the official narrative about the Colorado and dam that gave rise to the modern Southwest, Hiltzik mines well-studied areas for neglected detail.

Here the Los Angeles Times reporter strikes rich veins, offering vivid accounts of the settling and selling of the California desert, later the “Imperial Valley,” and the emergence of the doctrine of prior appropriation, our proudly impossible system of western water law born of the Gold Rush. Long, loving and often fascinating chapters are devoted to the political wrangling behind the Colorado River Compact and the Boulder Canyon Project Act. The alacrity with with Colorado’s Delph Carpenter realized that California’s six rival states on the river needed to act to protect their water is breathed back to life with flair and insight. A diversion into what became Arizona’s institutional truculence among the seven states on the river produces in George Hebard Maxwell a proselytizer whose emotional heat and extreme xenophobia would not be out of place in the state’s current immigration battles; yes, the rightful father of the Central Arizona Project was palpably nuts (and, Hiltzik nicely points out, a native Californian).

Highlighting interesting spots in this book could take a long time. Hiltzik’s chronicling of the dam’s construction is so studded with detail that he even devotes a page to obstacles faced by the Oregon-based landscape architect (Wilbur W. Weed) hired to bring roses and lawn to Reclamation headquarters in Boulder City.

That said, no review would be complete without touching on Herbert Hoover’s part in this dam, which is tenderly traced; if you haven’t felt sorry for the man most publicly held responsible for the Great Depression before, you might after reading this book. After more than a decade of heavy lifting to get the river states to stop quarreling and the dam built, the 31st president of the United States suffered the harrowing indignity of stepping into the shadows as his political rival and successor, Franklin D Roosevelt, inaugurated what was then the largest dam in the world.

That said, no review would be complete without touching on Herbert Hoover’s part in this dam, which is tenderly traced; if you haven’t felt sorry for the man most publicly held responsible for the Great Depression before, you might after reading this book. After more than a decade of heavy lifting to get the river states to stop quarreling and the dam built, the 31st president of the United States suffered the harrowing indignity of stepping into the shadows as his political rival and successor, Franklin D Roosevelt, inaugurated what was then the largest dam in the world.

Anyone seeking to understand how Los Angeles, San Diego, Las Vegas and Phoenix sprang from arid land should read “Colossus” — it is a mighty history for a colossal dam. But be warned: This strength is also its weakness. This very good book holds a strongly backward and often conventional gaze. The storied, exquisite and mysterious desert setting is described, when it is described, as a wasteland. It’s hard not to wince when tribes are bundled with endangered species, as if the rightful place of native Americans is being lumped with amphibians, flowers and all that. Mexico is but a back yard fence. Water left to flow its course is regarded as wasted. Then, grating for this reader, there is the ever-present issue of California’s narcissism and ingrained sense of entitlement. Hiltzik does a fine job sketching a balance of power so off kilter in the West that California could convince feds to build a dam in Nevada to bring the fresh waters of Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico largely to serve Los Angeles and the gloriously self-styled Imperial Valley of the California desert.

He further shows us how the Southwestern sunbelt was eventually born of a river whose flows were over-estimated, then over-allocated (and 20% of which evaporates every year), but offers little discussion of how it might survive its own formidable design flaws. As fascinating as it is to learn that Hoover Dam’s reservoir, Lake Mead, reached its all time record elevation of 1,225.44 feet on July 24, 1983 (and that the spillway concrete suffered), Hiltzik will need to write a sequel to address how to cope with the likes of Lake Mead’s elevation in July 2010, which opened today at more like 1,089 feet, or roughly 136 feet lower.

*This post has been updated. Random thoughts have been added and the closing elevation checked against Reclamation records.

Click here for closing June elevations of Lake Mead for the last ten years

Tags: chance of rain > Emily Green > Lake Mead elevations > US Bureau of Reclamation

Everything’s broken

Posted on | June 30, 2010 | No Comments

"La Dragona del Jardin" in the Echo Park garden of Larry Nichols and Rob Kibler. Photo: R Daniel Foster (reproduced with permission). Click on La Dragona to be taken to Foster's story "A smashing success" in the Los Angeles Times.

By now you may have read that the Governor of California and a good number of state legislators want to spare voters the trouble of considering an $11bn bond measure to pay for the package of water bills that they passed last November. After describing passage of the bills as “historic” and “herculean” last fall, the same men who told us that it had to be done because our water supply was “one earthquake, one flood away from collapse” have now decided that disaster can wait. We’re not scared enough to pay what it will cost to plan for it. For details, go to Aquafornia. My own response is to begin a grass roots campaign for La Dragona for Governor and Fifi D’Orsay for her lieutenant, along with planning a mosaic project for the weekend. The inspiration: A delightful piece of garden writing, “A smashing success” by R Daniel Foster.

Foster’s piece about the mosaics on the Echo Park property of Larry Nichols and Rob Kibler captures a garden that runs as much on imagination as water. It bears stressing that, according to Foster, the inspiration for Kibler, former head of Glendale Community College’s ceramics department, and Nichols, a former art director, was not water conservation, but the Northridge earthquake, which turned their ceramics collection into grist for the likes of La Dragona, above and Fifi (below). The excitement at how this kind of project could relieve garden plants (and therefore irrigation) of producing year-round color is mine. Otherwise, credit for an indomitable celebration of beauty and fun in the aftermath of disaster belongs to Foster, Kibler and Nichols. Click here for the Times photo gallery of the Nichols-Kibler garden. Also check out Foster’s website.

This bench was modeled after Fifi D'Orsay, who played naughty French girls in 1930s Hollywood movies. Photo (copyright) R Daniel Foster. Click on the image to be taken to his website fosterimage.com

Fifi was celebrated in a suitably saucy way. Photo (copyright) R Daniel Foster. Click on the image to be taken to Fifi's IMDb entry.

Tags: chance of rain > Larry Nichols > mosaics > R. Daniel Foster > Rob Kibler

The week that was: Fracking special

Posted on | June 28, 2010 | 3 Comments

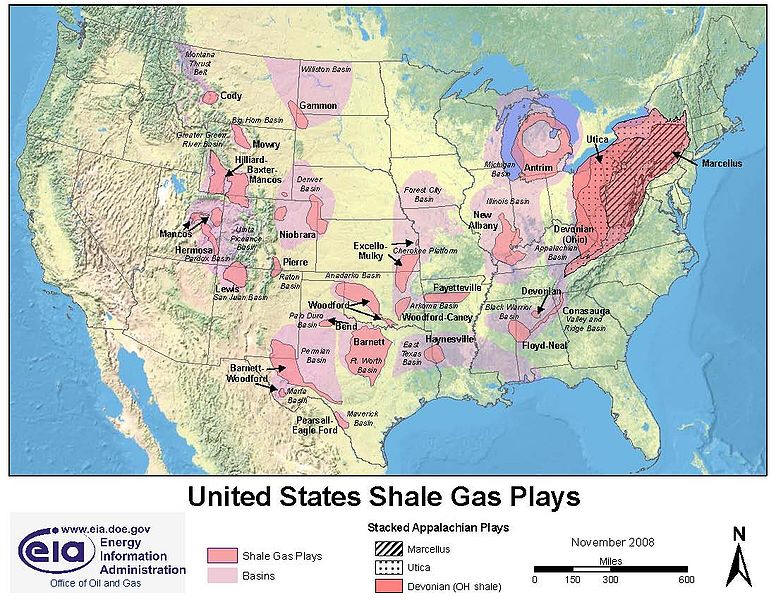

To read about how advances in hydraulic fracturing technology led geologists and energy companies to believe that a previously uneconomic source of natural gas might be tapped in the Marcellus Shale and Appalachian Basin, click on the map to be taken to an overview from Geology.com

Josh Fox’s documentary “GasLand,” broadcast last Monday on HBO, planted the suggestion that as former Vice President Dick Cheney was waging his “war on terror” in the wake of 9/11, his energy task force set America on a path capable of poisoning the drinking water supply of New York City, along with that of Pennsylvania, Delaware, parts of Ohio and West Virginia.

In May 2001, the report of the National Energy Policy Development Group gathered by former Halliburton CEO and then Vice President Dick Cheney concluded, "Most new gas wells drilled in the United States will require hydraulic fracturing." Click on the blue highlighted recommendation to be taken to the report.

Were the charge directed at almost anyone else, one would have to dismiss it out of hand, but Mr Cheney’s track record begs the question: How bad is it? I decided to check for myself and spent a week on ProQuest, a database available to just about anyone with a library card and access to a computer. The result is this cross-section of articles, announcements and reports on the gas extraction technology known as hydraulic fracturing, “fracing” or “fracking.”

The links after the jump offer but a snapshot of the gas drilling boom that Mr Cheney surely helped to migrate from Texas throughout the Intermountain West, West, Southwest and South into the Northeast. Many of the cited articles come from the Tulsa-based publication Oil & Gas Journal, which captured an angle missed by every other organ — that being how hotly the gas industry was concerned with keeping natural pollutants out of its fracking water just as the public began panicking about fracking chemicals in its drinking water.

Some ProQuest searches turned up only page after page of patent application notices for fracturing chemical recipes, a wildly lucrative area to judge by a $98m lawsuit brought in a Texas case involving Halliburton.

Honing in on the Northeastern boom, Pennsylvania State University is so deeply involved with the gas industry that it’s hard to know where one stops and the other begins. If there is a father of the rush into the Marcellus Shale, it is probably Penn State geologist Terry Engelder. His home page carries a 2008 UPI report valuing his scientific contribution to “U.S. energy resources by a trillion dollars, plus or minus billions.”

Water takes a back seat in this world of decimals and dollar signs. This 2009 PSU extension sheet on water needs of hydrofracking quotes “regulators” estimating that gas operations in the Marcellus Shale will be “roughly 10 billion gallons per year.” This is unconvincing. The state’s Department of Environmental Protection reports 3,917 wells permitted since 2005. Those alone could account for nearly 12bn gallons of water and nearly 60m gallons of fracking chemicals already in the system over the last five years, provided that the gas wells have only been fracked once. Given that the whole point of the process is that regular re-fracking can keep recalcitrant wells productive, and new wells are being permitted all the time, the 10bn gallons a year estimate looks meaningless, trashy even. This much the industry will tell us about what’s in those tens, probably hundreds, of millions of gallons of fracking chemicals: In 2004, it agreed to stop fracking with diesel. (February 16, 2011 update: A January, 2011 congressional investigation reveals that this didn’t happen, and that between 2004 and 2009, frackers used more than 32m gallons of diesel, half in Texas, also roughly three million gallons respectively in Louisiana, Oklahoma, North Dakota and Wyoming and more than a million in Colorado.)

Depressingly, the coverage of fracking and America’s natural gas boom was most remarkable for the absence of discussion about the role that conservation might play as the US searches for energy sources to bridge the transition from fossil fuels to something less punishing for the planet. This made me wonder if in Mr Cheney we might not have had the Vice President we deserved.

The week spent on ProQuest reading about fracking also convinced me that whoever is editing the Wikipedia entry is seriously on the ball.

For more on an Obama administration Environmental Protection Agency review on hydraulic fracturing, click here. To follow progress on the Frac Act now before Congress designed to undo the infamous “Halliburton clause” of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and to require oil and gas companies to disclose the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing operations, click here.

Click here for more on hydraulic fracturing

Tags: chance of rain > Emily Green > fracing > Fracking > hydraulic fracturing